My 8 principles for agentic coding

The shift from AI coding to agentic coding is a shift in identity

Hey friend,

I’ve been coding for 20 years. I’ve written code in Scala, OCaml, Lisp, Ruby, Python, Java; I genuinely love the craft. But lately, I’ve had to rethink what that craft actually is.

AI coding was phase one - AI helps you write code faster, but you’re still driving every decision. Useful, but limited.

We’re in phase two now. Agents (like Claude Code) that plan, execute, test, deliver. You review what comes back. The job is moving up the stack: building systems that write better code than you could write yourself.

The shift from AI coding to agentic coding is a shift in identity.

You’re not a developer who uses AI tools. You’re an engineer who builds systems that build software.

Here are the 8 principles that finally made it click for me.

1. Your Agent Is Capable But Contextless

Agents can read codebases, edit files, run terminal commands. They’re genuinely capable.

But every session starts empty. No memory of your architecture. No understanding of your conventions. No awareness of what you tried yesterday.

Before getting frustrated that “AI sucks”, ask yourself: does the agent have everything it needs to succeed without me? If yes, let it run. If no, either provide the missing context or plan to stay in the loop.

2. Plan First, Execute Second

This is probably the biggest unlock: don’t ask the same agent to plan the work and do the work.

When you tell an agent to “build feature X,” it tends to rush. It makes assumptions. It starts coding immediately and wanders.

Instead, use a two-step process:

Plan: Ask an agent to analyze the problem and write a plan. Review it. Iterate until it meets your standards.

Execute: Start a fresh session. The new agent reads the approved plan and executes with focus.

The pattern: Plan → Review → Execute (new terminal session) → Ship.

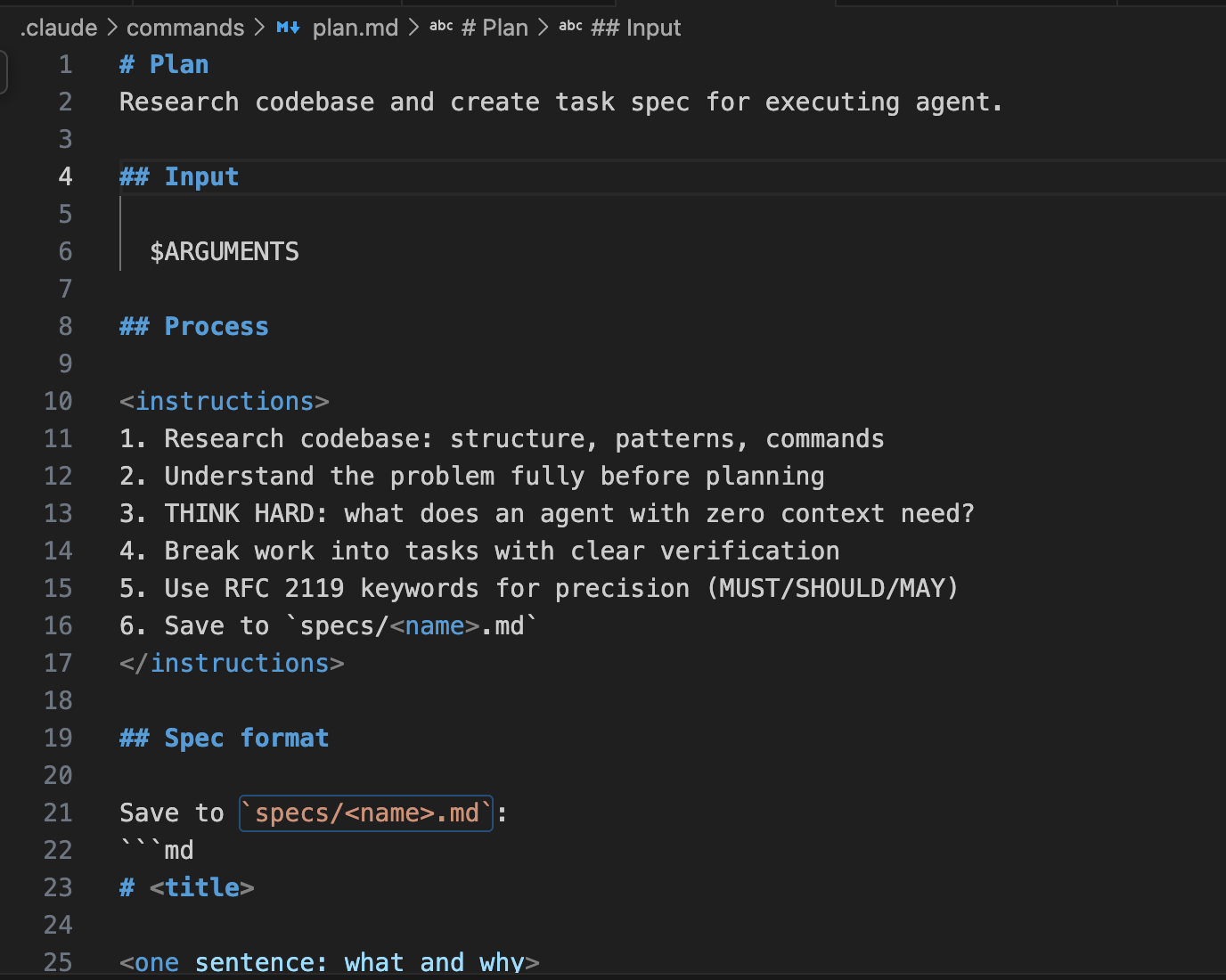

Here’s an example of Claude Code command to generate a detailed plan from a high level instruction.

> /plan create a new python project for a rag agent using postgresql and hybrid search.Iterate on the plan

> Update the plan to use uv for package management. Use Gemini as the model. Skip frameworks and use the SDK directly. Match spec weight to task weight. Most tasks are small. The spec should be too.

3. Match Your Involvement to the Task

Not every task needs the same level of attention.

Low Ambiguity: Writing a unit test, adding a standard endpoint, fixing a lint error. Hand these off completely and go get coffee.

High Ambiguity: Designing an auth system, refactoring core abstractions, debugging race conditions. Keep these in the loop; treat it like pair programming.

The goal isn’t maximum autonomy everywhere. It’s spending your attention where it matters.

4. The SDLC Still Applies

The software development lifecycle didn’t disappear. It just runs differently with agents. Plan, code, test, review, document: agents can handle all five phases if you set them up for it.

The mistake I see: skipping straight to code. When agents plan first, they execute better. When they test their own work, they self-correct.

5. Stack Your Leverage Points

A few things multiply your agent’s effectiveness:

Context files. A README, a conventions doc, an AGENTS/CLAUDE.md. If it exists in a file, you don’t have to explain it in prompts.

Runnable tests. This is the highest leverage thing you can provide. If an agent can run tests and see green or red, it validates its own work without waiting for you.

Concrete plans. A good plan includes verification steps. When “done” is defined by a passing test, the agent knows when to stop.

Reusable workflows. Solve a process once, save it. Planning, testing, shipping-each becomes something you invoke rather than explain.

6. Write for Agents, Not Humans

Documentation for humans assumes shared context. Documentation for agents needs to be blunt and assume nothing. Provide commands to run. Don’t be vague. Define success criteria concretely.

7. Encode Your Workflows

If you’re typing a long, complex prompt more than twice, save it.

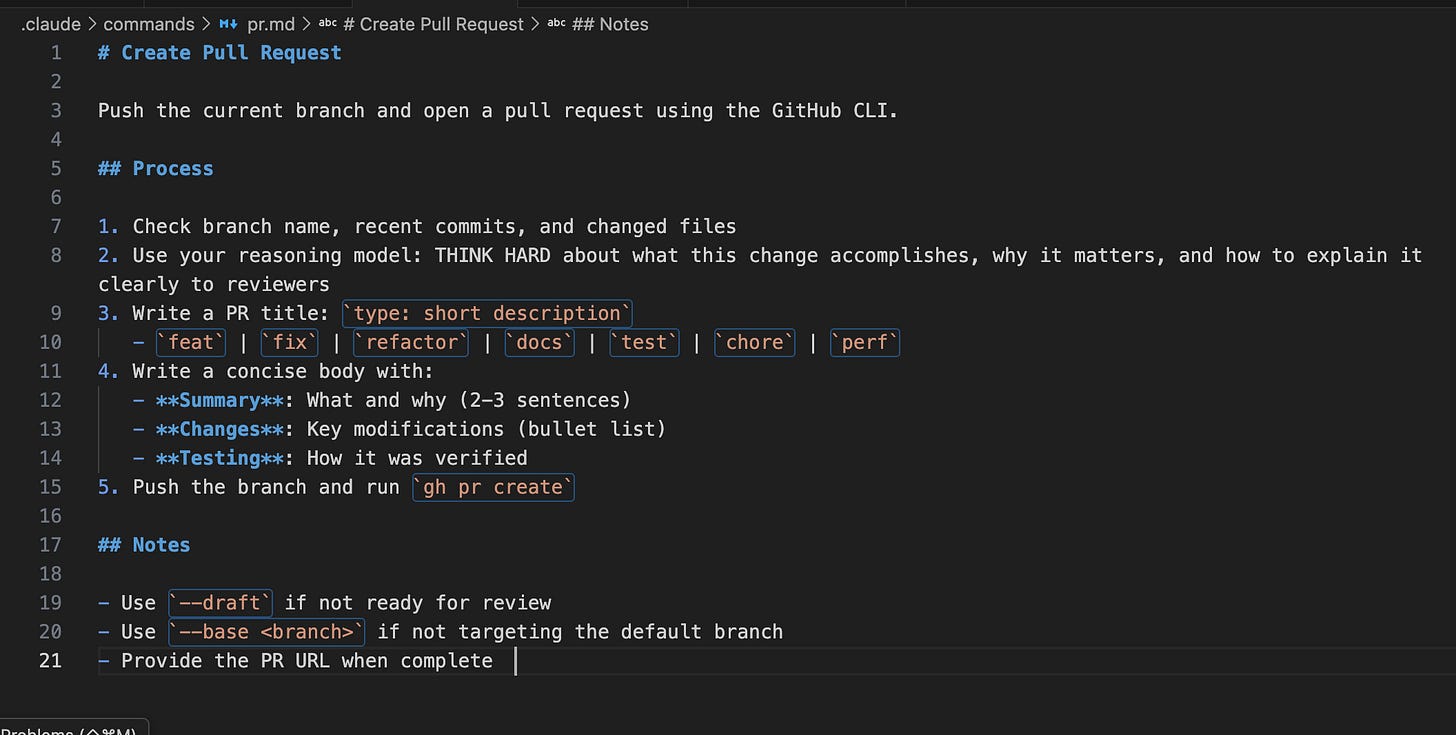

Here’s an example: a workflow I use for creating pull requests:

Check branch name, recent commits, and changed files

Think hard about what this change accomplishes and why

Write a PR title and concise body with summary, changes, and testing notes

Push the branch, run gh pr create, return the URL

I type one command, the agent handles everything. Five minutes to write, hundreds of uses afterward.

Pair a planning workflow with an execution workflow and you have a system: Plan → Build → Ship.

8. Measure Your Progress

How do you know you’re getting better at this?

Longer autonomous runs: The agent works for 10 minutes without asking a clarifying question.

Fewer iteration cycles: Tasks complete in 1-2 rounds instead of 5-6.

Higher first-try success: Tests pass without manual fixes more often.

When the agent gets stuck, don’t just fix the code-fix the workflow so it won’t get stuck there next time. That’s how you improve a system.

Thanks for reading.